Jack Ruch is one of my favorite guitar YouTubers because of his beautifully lyrical phrasing and excellent teaching style. He recently released a tribute to the late great Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers Band, which I highly recommend checking out. I’ll include a link at the end of this lesson, but I think you’ll get more out of Jack’s video if you read this first.

In the video, Jack demonstrates how Dickey Betts often added a 4th to the major pentatonic scale to create a hexatonic scale. It’s a signature part of the Allman Brothers’ sound, and it’s easy to learn and put into practice if you have the right framework.

In my video on the pentatonic scale, I break it down into two simple shapes called the rectangle and stack. These shapes are the same for both the minor and major pentatonic scales, except that the roots are in different locations, so the intervallic function of each note is different. For this lesson, we’ll be working with the major pentatonic scale.

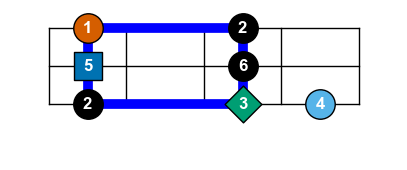

Here are the two shapes we’ll need, with the intervals of the major pentatonic scale filled in:

In my video, I show how you can add the b5 to the minor pentatonic scale to make the blues scale and how you could instead add the natural 2nd to it to create a beautiful minor hexatonic scale. In this case, we’ll do the same thing, except with the 4th and the major pentatonic. When we add it, we get these updated shapes:

This modified scale sounds slightly ambiguous to the ear. It’s richer than the major pentatonic on its own, but it doesn’t have a 7th, so it sounds a little more open than a full seven-note scale. Since the missing 7th could be either major or minor, your ear floats somewhere between hearing Ionian and Mixolydian. It’s a cool effect, similar to how the minor hexatonic scale fits in both Dorian and Aeolian contexts.

All of Jack’s examples are played over a G major vamp, and his lines move fluidly from stack to stack across the fretboard, sticking closely to the G major pentatonic scale. As a reminder, stacks connect diagonally, and if the fretboard had lots of strings that were all tuned to be five semitones apart, they’d look like this:

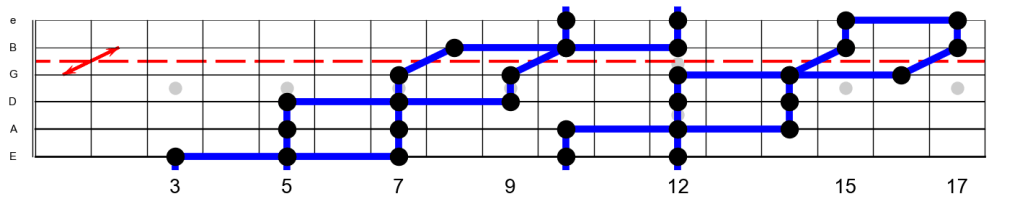

In practice, we have to take into account the four-semitone distance between the G and B strings, which I fondly call “the warp.” We end up with two extended fingering patterns for G major pentatonic:

When we choose to add in the 4th, it’s worth remembering that along with the 4th that sits just to the right of the bottom of the stack, there’s another one just above the root at the top of the stack. Although Jack’s lines mainly stick to the stack pathways shown above, when he reaches for the 4th, he often plays the 3rd and 4th from the upper neighbor rectangle, as shown here:

That’s all you should need to get the most out of Jack’s lesson and to be able to come up with lines of your own.

Here’s Jack’s video (and check out his Patreon for tab and backing tracks):