If you think of your diatonic modes in terms of the “grand unifying” patterns for in-position or 3nps scales, it’s easy to shift into on-the-fly harmonies within any of the seven modes, anywhere on the fretboard. The masters of counterpoint from Bach’s era realized that parallel harmonies in 3rds and 6ths sounded much better than any other parallel interval, and 3rds and 6ths harmonies can be found all over the place in rock music, so we’ll focus on those.

The key to unlocking this superpower is to be aware of the major scale degree of each note in the pattern.

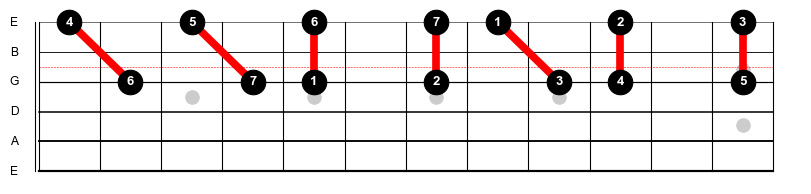

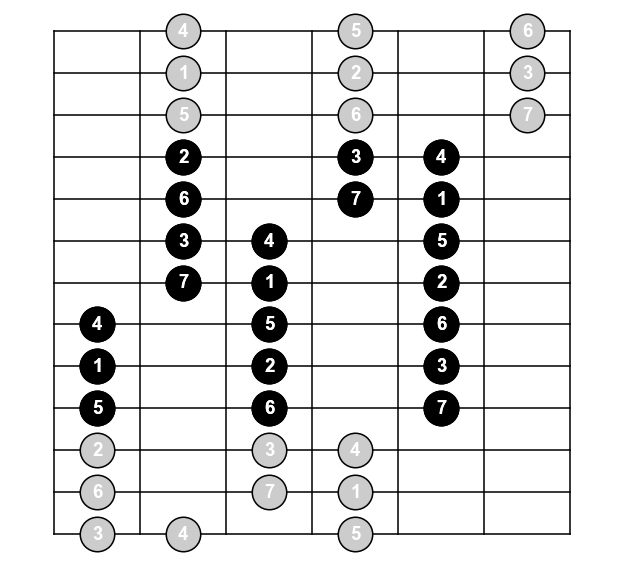

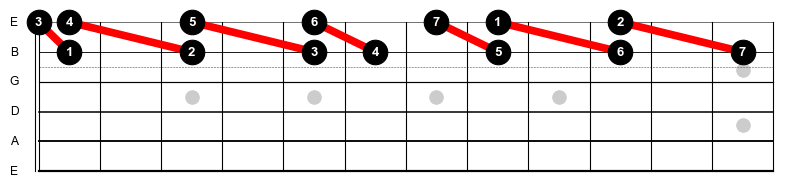

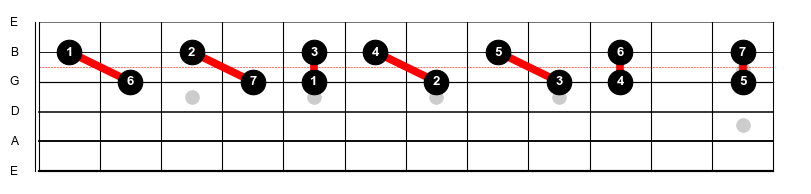

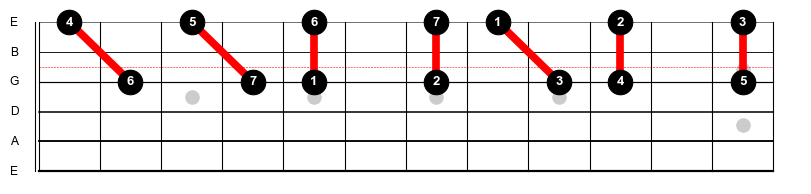

In Figure 1 and Figure 2, each note is labeled with the scale degree from the underlying major scale. As a reminder, all seven of the modes are contained in each of these patterns. If you play the sequence 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-1, you have played a major/Ionian scale. If you play 2-3-4-5-6-7-1-2, you have played the Dorian mode. To play the Phrygian mode, start on 3, Lydian=4, Mixolydian=5, Aeolian=6, and Locrian=7. For more on this, check out 3nps: One Pattern to Rule Them All and Learn to go from 3nps to “in-position” scales in 1 minute.

I recommend thinking of each of the 2- or 3-note single-string shapes by reference to the major scale degree of their lowest note. In Figure 1, reading up the first notes of the repeating pattern from bottom to top, we have 5, 1, 4, 7, 3, 6, 2. In Figure 2, it’s 6, 2, 5, 7, 3. You can always figure out the other notes by counting upward along a string and remembering that after 7 comes 1.

Now that you know where you are in the pattern, in terms of major scale degree, how do you create harmonies?

Well, first it helps to understand what we mean by a 3rd or a 6th interval. Within the sequence of notes in the major scale (or any of its modes), an interval of a 3rd is formed by playing one note, skipping the next, and playing the following note, either in sequence or at the same time. The distance between the two notes will always be three or four semitones/frets. If it’s three, we call the interval a minor third, and if it’s four, we have a major third.

If you play a third going up the major scale starting from the first, fourth, or fifth scale degree, you will get a major third. Starting from the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, or 7th scale degree will yield a minor third. Putting these in order and substituting “M” for major and “m” for minor, we get the “MmmMMmm” from the title of this post.

Now we’re cooking.

3rd interval geometry on adjacent strings

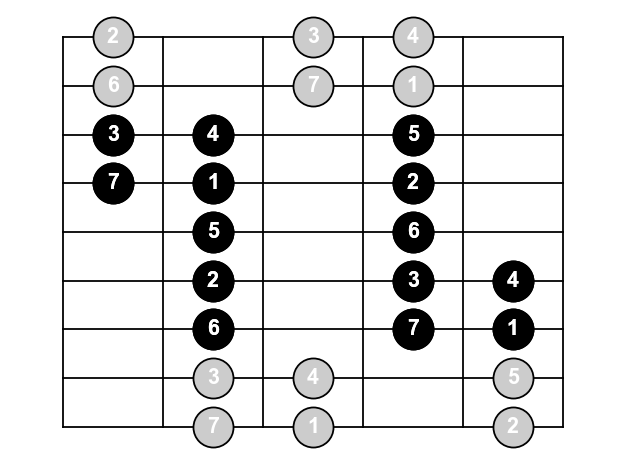

Major and minor thirds are easy to play on any pair of adjacent strings if you know the right geometric shapes. In all of the figures that follow, I’ve drawn a red line between each pair of notes for clarity.

As you can see in Figure 2, a major 3rd is up one string and down one fret, and a minor 3rd is up one string and down two frets. This works everywhere on the fretboard, except between the G and B strings, as shown in Figure 4.

Now, if you know the pattern for the underlying major scale along one string, you can create 3rd interval harmonies by applying the correct type of 3rd interval based on the scale degree. Again, 1, 4, & 5 are major, and everything else is minor.

Figure 5 shows how to do this with the C major scale on the B string. If you focus on playing the correct notes on the B string and you use the scale degree to create the correct minor and major 3rds on the E string, you don’t have to memorize the notes on the E string; you can reconstruct them on the fly.

And, of course, you can use this trick on any pair of adjacent strings, but remember to account for the major third interval between the G and B strings, as shown in Figure 6.

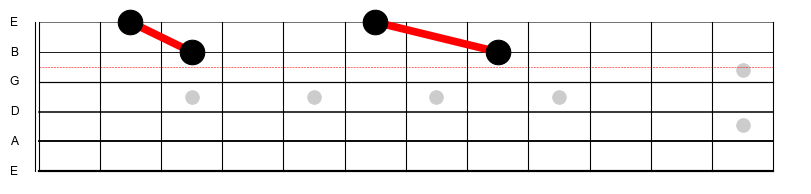

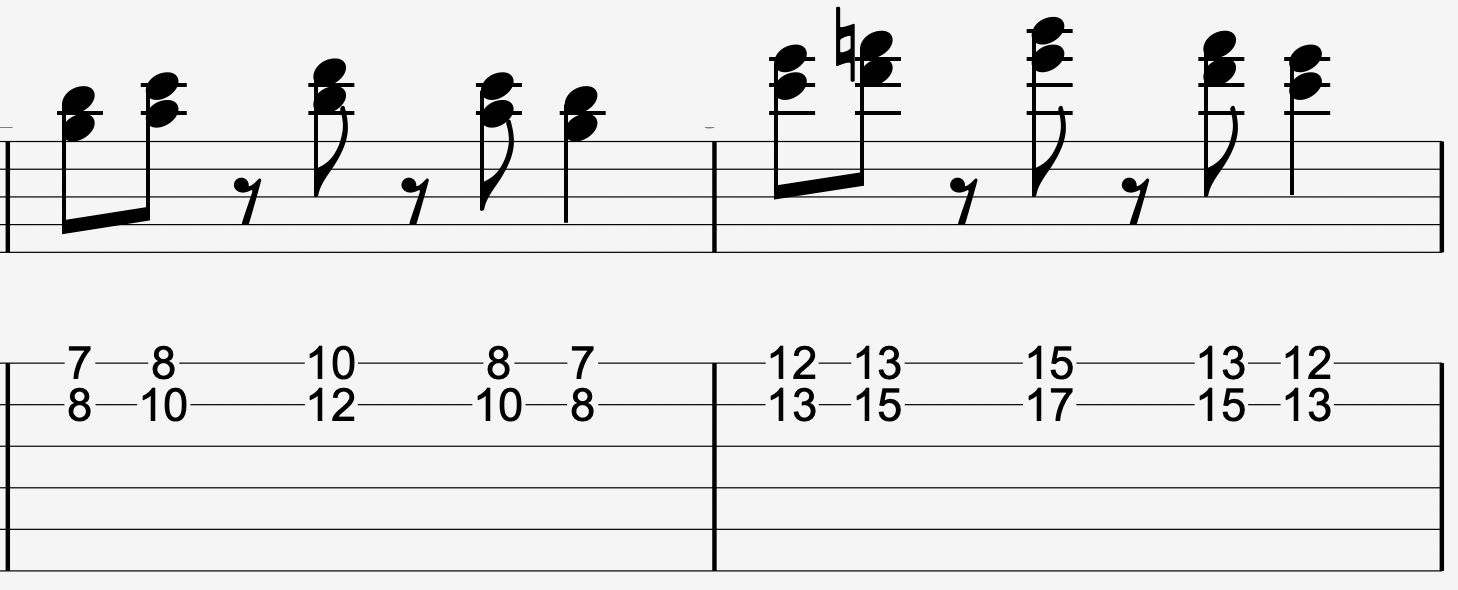

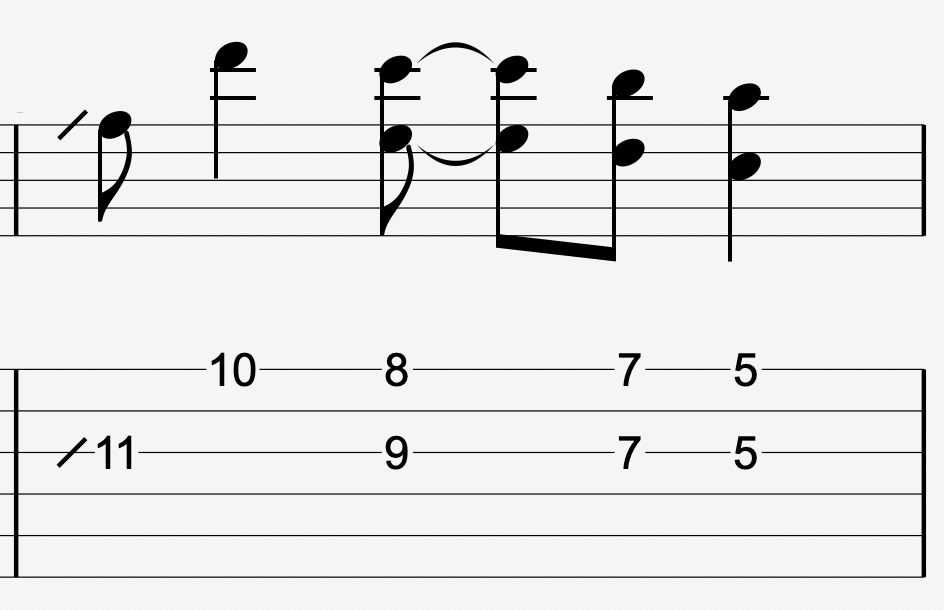

Example 1: “Brown Eyed Girl” intro

The introductory lick to Van Morrison’s Brown Eyed Girl is straight-up diatonic 3rds harmony with a very slight twist. Although the tonal center of the song is G major, the opening lick is in G Mixolydian, meaning that G would be considered to be the fifth scale degree of the parent C major scale. Another way of saying this is that although the key of G normally contains an F#, this lick has no sharps or flats.

The first measure of the lick is played over a G Major triad, and is 3rds harmony starting on the G note at the 8th fret of the B string. Considering G to be the fifth scale degree, you can think of this lick as playing the first three notes of the G Mixolydian scale (or the 5th, 6th, and 7th scale degrees of the C major scale) along the B string, and also playing the appropriate thirds on the E string:

The second measure is played over a C major chord, and the pattern is repeated exactly, but this time basing the intervals off of the 4th, 5th, and 6th notes of the G Mixolydian scale (or the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd scale degrees of the C major scale).

My suggestion when working with modes is to think in terms of the scale degrees of the parent major scale, but always know where the tonal center is. For Ionian/major, it’s the first scale degree; for Dorian, it’s the second; Phrygian, 3rd; Lydian, 4th; Mixolydian, 5th; Aeolian/minor, 6th, and Locrian, 7th.

6th interval harmonies made easy

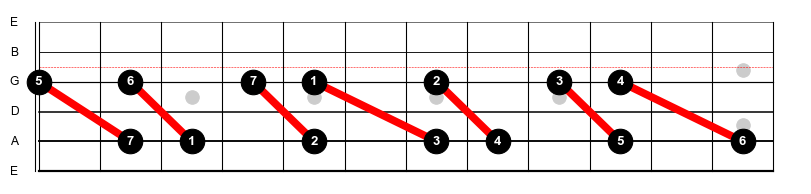

We can use the same approach with 6th intervals.

It turns out that, because there are seven notes in the diatonic scale, if you go down five scale degrees instead of up two, you get to the same note, but you get spans of eight semitones/frets (a minor 6th) if you start from the first, fourth, or fifth scale degree, or 9 semitones/frets (a major 6th) if you start from the 2nd, 3rd, 6th, or 7th scale degree.

The result is that a major 3rd ascending interval involves the exact same notes as a minor 6th descending interval, and a minor 3rd ascending interval involves the exact same notes as a major 6th descending interval.

Figure 8 shows how to do this with the C major scale on the G string. If you focus on playing the correct notes on the G string and you use the scale degree to create the correct minor and major descending 6ths on the A string, you don’t have to memorize the notes on the A string—you can reconstruct them on the fly.

Even though these are 6th intervals, I prefer to think of them as inverted 3rds. I focus on the higher string, and I know that if I’m starting from the 1st, 4th, or 5th scale degree, the correct note will be two strings lower and two frets higher. If I’m starting from one of the other scale degrees, the correct note is just one fret higher.

These intervals are most commonly used on either the E and G string set or the B and D string set, which both overlap the dreaded G-B string pair. Figure 9 shows the harmonization of the E string C major scale with descending 6ths.

Again, when playing these patterns, I keep my focus on the E string and keep track of which scale degree I’m on. If it’s 1, 4, or 5, I also play the note two strings down and one fret up. If it’s 2, 3, 6, or 7, I play two strings down on the same fret.

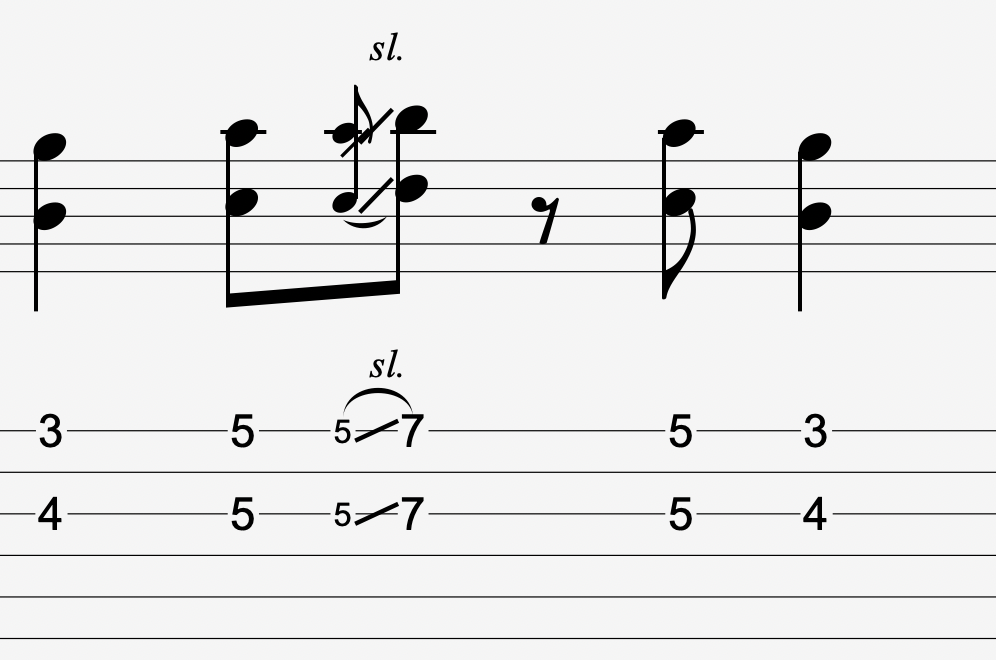

Example 2: more “Brown Eyed Girl”

There are millions of licks and fills that use parallel 6ths harmonies on either the E and G or B and D strings. Here are two small tasty examples from Brown Eyed Girl that are easy to understand and play.

In measure 12 of Brown Eyed Girl, the lead guitar plays the fill shown in Figure 10 over a D major triad.

I think about this lick as being focused on the D note at the 10th fret of the E string. This note is the 5th scale degree of the G major scale that underlies the whole song (excepting the G Mixolydian opening riff as discussed in Example 1).

Keeping the 10th fret of the E string in mind, the lick slides into the “major 3rd” on the G string, and then walks down the scale on the E string, playing the correct major and minor thirds on the G string. The C note on the 8th fret is the 4th scale degree, and the B and A notes at frets 7 and 5 are the 3rd and 2nd scale degrees.

In measure 17, the lick follows the same logic, but starts with the G (1st scale degree) at the 3rd fret of the E string, and walks up to the 2nd and 3rd scale degrees and then back down.

Although it may not be obvious at this point, the major scale degree ends up being the Rosetta Stone that allows us to pivot between the “languages” of: 3rds & 6ths harmonies, diatonic modes (both horizontally and vertically), and pentatonic scales. It’s highly worthwhile to learn this mental model if you want to be able to move freely around the fretboard.