This post is going to get a little abstract before it gets practical, but if you bear with me, it’ll be worth it. In the end, there will be no box to break out of, just a fretboard full of pentatonic goodness from bridge to nut.

Most guitarists learn the pentatonic scale as five separate two-notes-per-string fretboard patterns. Then they struggle to connect those patterns fluidly, and they are forced to learn which notes sound good in each of the patterns separately.

Instead, it’s helpful to think of every pentatonic pattern as being made up of a combination of two recurring sub-patterns that we’ll call “the rectangle” and “the stack”. If you’ve followed along on Fret Science, you’ve already been introduced to “the rectangle” as a pivot between pentatonic scales and their related diatonic modes and as a shortcut for playing the diatonic modes on a pair of strings.

[The scare quotes on “the rectangle” and “the stack” are going to get old pretty quickly, so I’m removing them from here on out and using italics, which hopefully will be less annoying.]

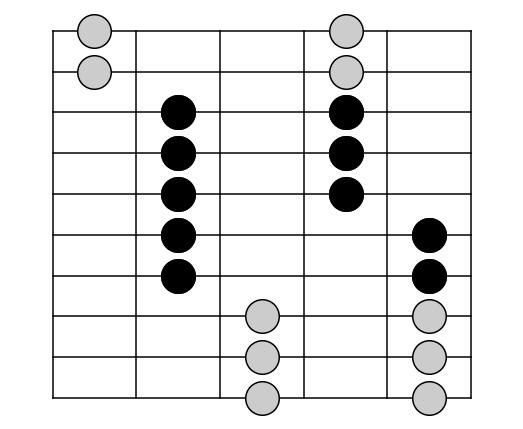

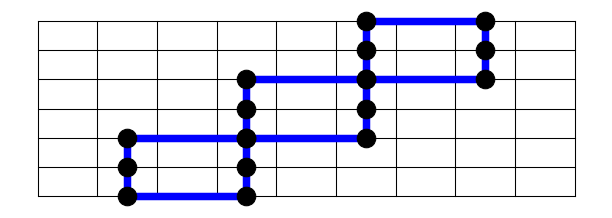

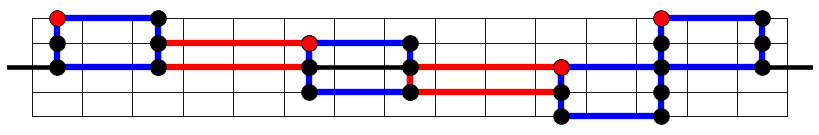

To start, let’s consider a two-note-per-string pentatonic pattern on an imaginary fretboard with infinitely many strings, all tuned in 4ths. The 2nps pentatonic pattern repeats every five strings:

Take any group of six adjacent strings from Figure 1, slide the top two strings up one fret, and you’ve got one of the standard pentatonic forms.

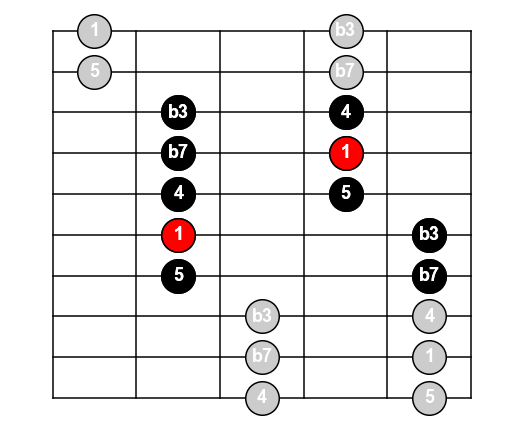

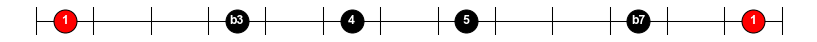

What distinguishes a major pentatonic scale from a minor pentatonic scale is not the notes — they’re exactly the same. It’s where the tonal center falls in the intervallic (and hence geometric) pattern. There are five possible choices, and we commonly use two of them:

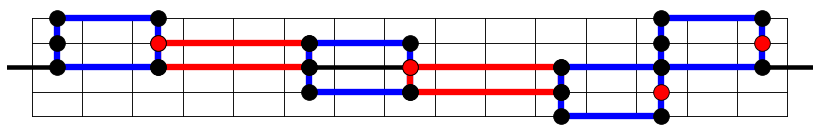

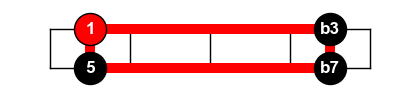

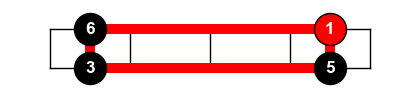

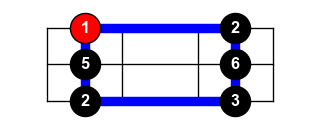

In previous posts, I have talked about the rectangle — a shape within two-notes-per-string pentatonic scale patterns that is present in all of the five common pentatonic forms. The rectangle makes it easy to switch between pentatonic scales and six of the seven diatonic modes. In all of the following figures, the rectangle is shown in red.

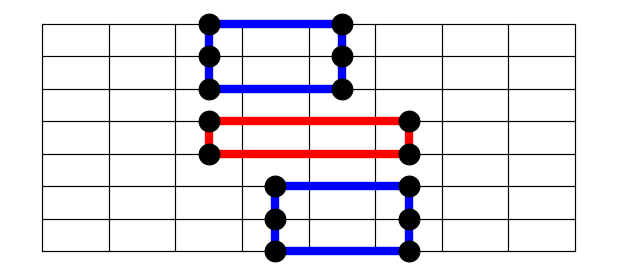

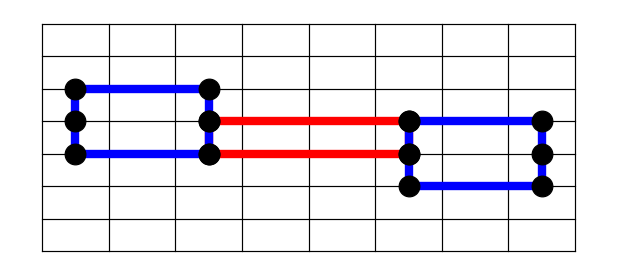

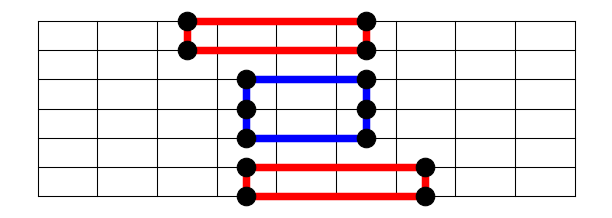

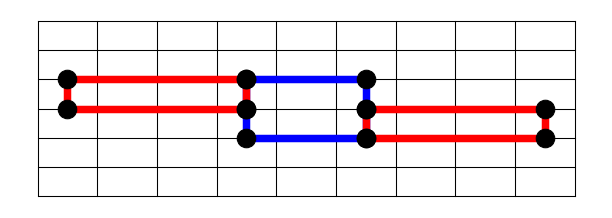

The rectangle occupies two strings of the five string repeating pattern. The other three strings in the pattern contain a shape I heretofore dub the stack, in honor of its shape, as well both the amplifiers we play it through and the venerable computer architecture component your computer/phone uses to run the web browser you’re reading this in. In the following figures, the stack is shown in blue.

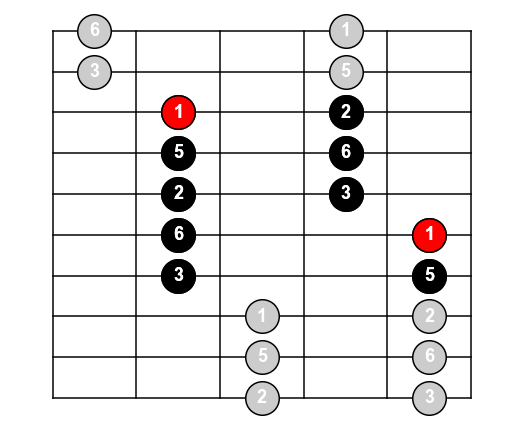

Regenerating the five pentatonic forms

Although I’m not a fan of explicitly memorizing the five six-string pentatonic forms, it’s worth seeing how the rectangle and the stack show up in each of them. Each of these forms is simply a set of six adjacent strings from the “grand unifying” pattern subjected to the warp imposed by the major 3rd interval between the G and B strings.

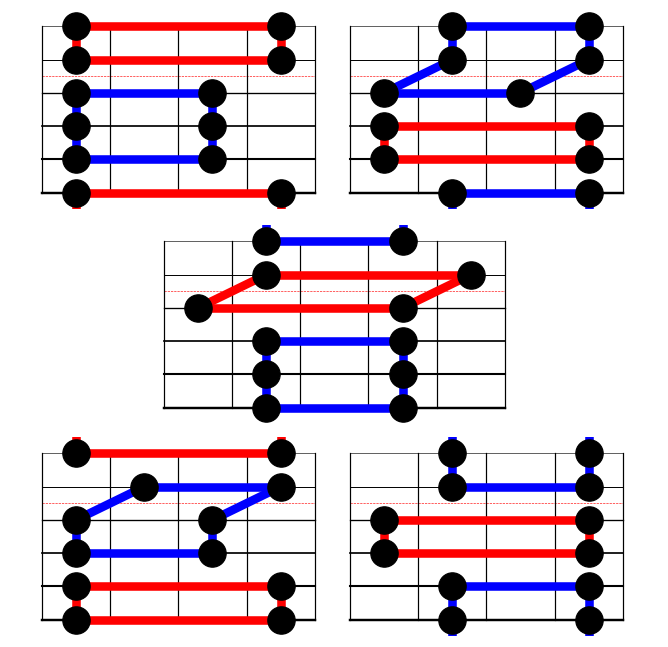

Moving around the fretboard

The key to moving around the fretboard within a pentatonic scale is to know whether your fingers are on the rectangle or the stack, and how those shapes connect to each other, both horizontally and vertically.

If you already know the five 2nps pentatonic forms, great! If you’ve ever had difficulty remembering how they connect together, look for the rectangle or the stack inside the form and use the horizontal connections shown above.

Navigating along one string

Another useful navigational technique is to be able to play an arbitrary distance horizontally along a single string to get from one position to another, and then to quickly reorient vertically to the pentatonic scale in the new position.

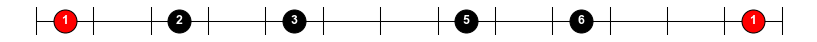

The pentatonic scale has five intervals: two minor thirds (3 frets), and three major seconds (2 frets). For the minor pentatonic scale, it looks like this:

I have found it useful to visualize how the stack intersects each of the major second intervals, and how the rectangle intersects each of the minor thirds. If we label the strings of each shape with two letters (TS = top of the stack, MS = middle of the stack, BS = bottom of the stack, TR = top of the rectangle, BR = bottom of the rectangle), the sequence is TR, TS, BS, BR, MS, repeating.

The major pentatonic scale has the same sequence of intervals, but it starts and ends at a different point in the sequence.

For the major scale, the sequence of labels is TS, BS, BR, MS, TR, repeating. This is the same pattern as for the minor scale, but it starts on the second label in the minor scale’s cycle.

Playing major vs minor

Now that we have seen how the rectangle and the stack are positioned relative to each other both horizontally and vertically, how do we make music with them?

Rather than the traditional way of learning to make music from minor and major pentatonic scales in five patterns (a total of 5×2=10 configurations), using this method, we can learn to make music from the minor and major variants of the rectangle and the stack (2×2=4 configurations). Since these configurations also contain 4 and 6 notes each rather than 12 notes each, this is approximately an 85% mental savings! Not only that, but this system is trivially extensible to 7- and 8-string guitars, as well as 4-, 5-, and 6- string basses.

I like to mentally access these shapes according to whether my index finger or ring finger is on the tonal center of the scale. In a minor context, if my index finger is on the tonal center, I’m playing the rectangle, and the stack starts on the next string up.

If my ring finger is on the tonal center, I’m playing the stack.

For the major pentatonic scale, the finger positions are reversed.

Next: learn the blues scale across the entire fretboard in under one minute.