Moving chord and scale patterns around the fretboard is simpler than it seems.

In standard (EADGBE) tuning, adjacent strings on a guitar are mostly tuned to be five semitones (or five frets) apart in pitch. That’s why, if you finger the fifth fret of the low E string, it yields the same pitch as the open A string. In the olden times, before the advent of cheap digital tuners, that’s how we tuned our guitars.

And this strategy works for all adjacent pairs of strings, except between the G string and B string, which are tuned to be four semitones apart. If you know your interval names, this a major third instead of a perfect fourth. I like to joke that the reason the G string always seems to go flat is that it’s trying to stretch out that interval to a perfect fourth.

At one level, this tuning system makes things needlessly complicated. Geometric patterns on the fretboard seem to get warped when they go across the boundary between the G and the B strings. Some guitarists, like fusion player Tom Quayle, use all-fourths (EADGCF) tuning, which makes scale patterns much simpler, at the expense of making many common open chords difficult or impossible to play.

And so, we ordinary guitarists suffer to understand fretboard geometry so that it’s easy for us to strum cowboy chords to Wonderwall. Yay, us.

How to visualize it

The trick to moving geometric patterns around the fretboard is that any part of a pattern that crosses the invisible line between the G and B strings will be shifted by one fret.

If the pattern moves from the G string side to the B string side, it shifts one fret up toward the bridge. If it moves from the B string side to the G string side, it shifts one fret down toward the nut. Let’s look at some examples to make this more clear.

When the familiar octave pattern crosses the G-B boundary, the upper note moves toward the bridge, turning a two-fret span into a three-fret span:

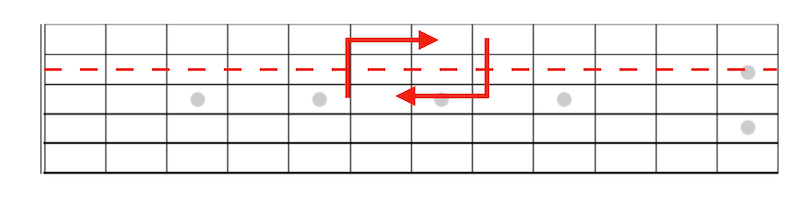

You may recognize the following rectangle pattern from when you learned the pentatonic scale for the first time. When it crosses the G-B boundary going toward the lower strings, the lower set of notes move one fret toward the nut, making a parallelogram shape:

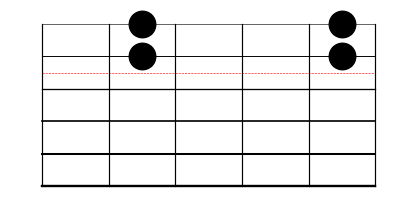

This effect also explains the difference in the shapes of the familiar major barre chords rooted on the 6th and 5th strings. Here, all of the fretted notes simply shift up one string (toward the high E), but the 3rd of the chord (marked in black), which moves across the G-B boundary, shifts one fret toward the bridge:

The exact same movement happens with the minor barre chords:

If you understand this simple mental model, it opens up new ways of understanding the major and minor pentatonic scales, the in-position forms of the major scale modes, and the 3nps scale system, but we’ll save those for another post.